Application of biologics in the treatment of the rotator cuff, meniscus, cartilage, and osteoarthritis.Abstract: "Advances in our knowledge of cell signaling and biology have led to the development of products that may guide the healing/regenerative process. Therapies are emerging that involve growth factors, blood-derived products, marrow-derived products, and stem cells. Animal studies suggest that genetic modification of stem cells will be necessary; studies of cartilage and meniscus regeneration indicate that immature cells are effective and that scaffolds are not always necessary. Current preclinical animal and clinical human data and regulatory requirements are important to understand in light of public interest in these products."

With respect to rotator cuff repair, however, the authors conclude that 'synthesis of all the studies illustrates that there is no clear advantage to using PRP (platelet rich plasma) as a surgical adjunct to rotator cuff repair'. A similar statement was made about mesenchymal stem cells.

Comment: While there is no question that platelets, growth factors and stem cells are part of the body's response to injury and healing process, there are many complexities in trying to improve on nature's finely tuned healing response.

As pointed out the

Rotator Cuff Tear Book, we consider rotator cuff repair when tendon of good quality can be brought to bone of good quality without undue tension on the repair. We then intentionally create a injury to the bone in the form of trough into which the tendon is secured. By creating this trough, we cause local bleeding and start the response to injury with the natural influx of platelets, growth factors, and stem cells.

Rotator Cuff 13 - Full thickness rotator cuff tears - repair

Full thickness rotator cuff tears are treated by secure reattachment to bone, provided there is sufficient quantity and quality of tendon for a robust attachment with the arm at the side. The goal is to have a smooth distribution of load that is continuous across both the repaired and intact tendon so that disproportionate force concentration on the repair is avoided. Because there is often a loss of tendon substance, repair to bone relatively shortens the tendon. The ability of the muscle to be extended laterally to accommodate for this shortening is limited by (1) the attachment of the capsule to the tendon on one hand and to the glenoid labrum on the other and (2) the attachment of the coracohumeral ligament to the tendon of the supraspinatus and subscapularis laterally and the coracoid medially. Thus, unless the tear is acute, it may be necessary to release the coracohumeral ligament from the coracoid.

and to release the capsule from its attachment to the glenoid labrum

so that the muscle and tendon can be drawn out further laterally to the insertion. Without such releases the repair may be under undue tension and at risk for failure. After the releases have been performed and after any scar has been dissected from the humeroscapular motion interface, traction sutures are placed in the tendon edge. If good quality tendon can be brought close to its normal insertion site with the arm in adduction, a robust repair can be carried out.

The ideal reattachment technique has the following properties:

(1) yields a smooth upper surface which can articulate congruously with the intact undersurface of the coracoacromal arch

and avoids knots or tendon edges on the upper aspect of the repaired cuff where they could rub under the coracoacromial arch

(2) excludes joint fluid from the repair site and accommodates some slippage in the sutures and knots without separation of tendon from bone

(3) creates a secure isometric junction between the tendon and bone spreading the load among numerous sutures

(4) can accommodate weakened bone at the greater tuberosity

(5) can be accomplished without sacrificing acromion, the acromioclavicular joint, or the deltoid origin

If there is insufficient quantity and quality of tendon to reach the tuberosity with the arm at the side, consideration can be given to moving the insertion site up to 1 cm medially on the humeral articular surface. If a robust repair cannot be performed, the priority shifts from repair to achieving the smoothest possible upper aspect of the proximal humerus for articulating with the undersurface of the coracoacromial arch. Often the head is translated superiorly because of the loss of the spacer effect of the superior cuff tendon and secondary erosion of the superior glenoid lip

This situation may call for smoothing of the upper aspect of the residual cuff as well as recession of the tuberosities if they are prominent so that the surface presented by the proximal humerus to the coracoacromial arch is smooth – we refer to this as a “smooth and move,” the goal of which is to convert the upper aspect of the proximal humerus into a smooth convexity that articulates congruously with the concave undersurface of the coracoacromial arch. Because the procedure is performed through a deltoid-on approach, no postoperative restrictions are placed so that the patient can move the joint actively immediately after surgery. We have found that when the cuff will not reach to a reasonable insertion site, abducting the shoulder so that repair can be achieved

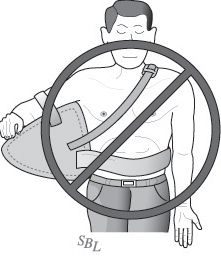

and then ‘protecting’ the arm in abduction

tends to lead to cuff insertion failure when the arm is brought down to the patient's side.